It’s the most profound, and most irritating, question of the 21st century. Not a riddle posed by a philosopher in an ivory tower, but a challenge from a disembodied server, presented in a slightly distorted font inside a small box. "Are you a robot?" it asks, demanding you prove your humanity by identifying traffic lights or clicking a checkbox.

We treat it as a trivial gatekeeper, a digital annoyance before we can access an article or buy a product. But I’ve come to view this simple prompt as the central query of our time, one that we should be aiming not at ourselves, but at the very architects of this new world. We spend our days proving we aren't bots to the machines. Perhaps it's time we asked the creators of those machines the same question.

The Architect as an Optimized System

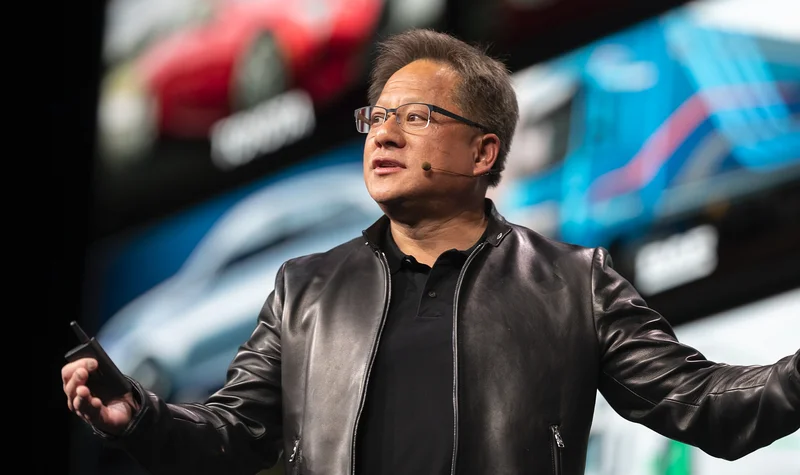

Let's start with the man at the center of the silicon universe: NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang. To watch him on stage is to witness a masterclass in signal clarity. Imagine the scene at the GTC keynote. The air in the San Jose Convention Center is thick with anticipation, a low hum of thousands of whispered conversations. Then, the lights dim, a massive screen flickers to life, and out walks one man in his now-iconic black leather jacket, the focal point of trillions of dollars in market value. Every gesture, every pause, every technical specification is delivered with a relentless, optimized precision.

The output is undeniable. The company's stock, NVDA, is up something like 200% this year—or, to be more exact, 239% as of last market close. This has catapulted Jensen Huang's net worth into a stratosphere previously reserved for heads of state and oil barons. His performance is a function, and the output of that function is shareholder value. I've analyzed hundreds of CEO presentations, and the sheer consistency of Jensen Huang's messaging is something I find statistically remarkable. It’s a level of discipline that borders on the programmatic. He has a core mission—to sell the hardware that powers the AI revolution—and every public statement, every product reveal, is a subroutine serving that primary directive.

Is this a critique? Not necessarily. It’s an observation of a system operating at peak efficiency. When you are the CEO of NVIDIA, a company whose market cap recently surpassed that of entire nations (a fact that still feels abstract), you cease to be just a person. You become a human-shaped vessel for a corporate mission. The Jensen Huang jacket isn't just clothing; it's a uniform, a constant variable in a world of chaotic market fluctuations. It signals stability, predictability, and a brand identity so consistent it could be an algorithm.

The Competitive Variable and the Shared Protocol

Of course, no system operates in a vacuum. For every action, there is a reaction, and in NVIDIA's case, that reaction is often initiated by AMD. The rivalry between Lisa Su and Jensen Huang is the defining narrative of the semiconductor industry. It’s often framed in personal terms, but from an analytical standpoint, it looks less like a human feud and more like two competing algorithms relentlessly iterating to outperform one another.

This is my analogy for their dynamic: they are like two grandmaster-level chess engines. They don't hate each other; they are simply executing their programming to win, optimizing every move based on the opponent's last action. The market is their chessboard, and their product launches are their moves. The persistent, unfounded rumors that Lisa Su and Jensen Huang are related speak to this phenomenon. People search for a human connection, a family drama, to explain a rivalry that is, at its core, purely mathematical. They are "related" not by blood, but by the immutable laws of market physics; one's success is an input variable in the other's strategic calculus.

This dynamic extends beyond just two individuals. When you see figures like Elon Musk enter the AI hardware fray, demanding tens of thousands of GPUs, he isn't just a customer. He's introducing a massive new data point that forces the entire system to recalibrate. The actions of these titans are so significant that they function less like the decisions of individual humans and more like protocol-level changes to the network itself. They set the parameters, and the rest of the market simply has to adapt. But what happens when the human element introduces an error term?

The Glitch in the Machine

For all the machine-like consistency, the human component can't be entirely suppressed. It occasionally surfaces as a "glitch"—an unscripted, unpredictable, or strangely humanizing moment that deviates from the main program. When Jensen Huang talks about the importance of plumbers and electricians, advising students to focus on skilled trades rather than coding, it feels like a deviation from the script. Here is the world's leading evangelist for a computational future suddenly championing the analog.

It's a fascinating contradiction. Is it a genuine belief, a calculated bit of public relations to appear grounded, or something else entirely? We have no data to confirm the motive, only the outlier itself. Similarly, when we see photos of tech CEOs meeting with political figures like Trump, the context collapses. The clean, logical world of silicon roadmaps and performance benchmarks collides with the messy, unpredictable world of human politics.

These moments are the system's error logs. They are the data points that don't fit the trend line, reminding us that behind the staggering net worth and the quarterly earnings reports, there is a person. But they also raise a crucial question that the data can't answer: Are these "glitches" a feature or a bug? Is the residual humanity a critical component that allows for genuine innovation, or is it just noise that the system has yet to fully optimize away? And as these leaders become more powerful, will the pressure to remain "on-script" and algorithmically perfect become so immense that these humanizing glitches become rarer and rarer?

The Turing Test for CEOs

Ultimately, the question isn't whether Jensen Huang or Lisa Su are literally robots. They are, of course, human. The more salient question is whether their function within the global economic machine has become indistinguishable from that of a highly advanced algorithm. An algorithm's purpose is to take inputs and generate a specific, optimized output. By that measure, the modern tech CEO is the most effective algorithm ever designed, with inputs of capital and engineering talent and an output of unprecedented market capitalization. We keep asking our computers to prove they aren't human. Maybe the real test is asking our leaders to prove they still are.