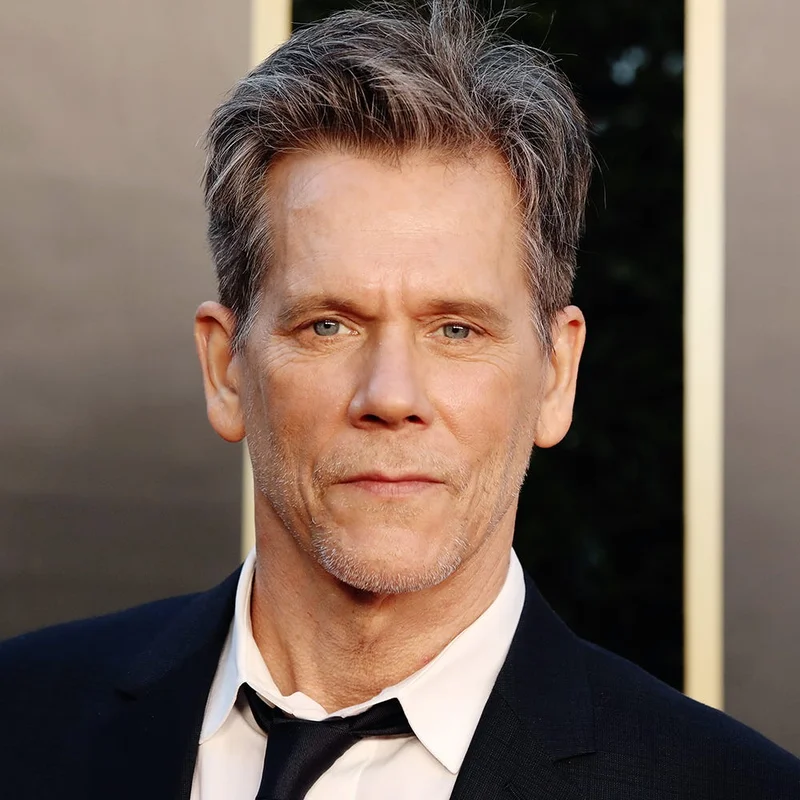

The career trajectory of a successful actor is often presented as a clean, linear progression: drama school, a few commercials, a breakout role, and then a steady accumulation of credits. It’s a narrative we’ve been conditioned to accept. So when an outlier data point emerges, it warrants closer examination. The case of actor Kevin Bacon presents such an anomaly. At the recent CREATE conference in Nashville, speaking alongside his brother Michael, Bacon referenced a formative period in his life that had nothing to do with acting coaches or film sets. It was his time as a waiter.

He described the job, which he held for about four years after moving to New York City at 17, as "the closest thing I had to college." This isn't just a quaint anecdote. For anyone analyzing career development and skill acquisition, this statement should be treated as a significant variable. The common assumption is that such jobs are merely a means to an end—a way to pay rent while pursuing a "real" career. Bacon’s framing refutes this. He posits that the four years he spent bussing tables and taking orders was not a holding pattern; it was the education itself.

This recasts the entire model of his early development. While a young Kevin Bacon was years away from roles in films like Footloose or Friday the 13th, he was engaged in a daily, high-volume study of human behavior. A restaurant is a compressed, chaotic ecosystem of characters, transactions, and micro-dramas. It's an unfiltered feed of human interaction. And this is the data point I find most compelling: for an aspiring actor, what is a more valuable education? The curated, theoretical environment of a classroom, or the raw, observational fieldwork of a New York City dining room?

The Restaurant as a Data Collection Engine

Let's deconstruct the "restaurant as college" thesis. A traditional university program provides structured knowledge. Bacon’s alternative provided unstructured, real-world data. He wasn't learning theory; he was observing humanity in its natural habitat. The regulars, the tourists, the demanding customers, the overworked kitchen staff—each interaction was a lesson in motivation, conflict, and resolution. This experience is less like a lecture and more like an immersive simulation. You can't learn the subtle tells of a person trying to impress a date, or the quiet desperation of someone dining alone, from a textbook.

This period of his life, roughly four years—or to be more precise, a duration he explicitly equates to a four-year degree—served as a crucial incubation period. It’s here that the famous “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” game finds a metaphorical origin. Long before he was a hub connecting every actor in Hollywood, he was a node in a much denser, more chaotic network of everyday people. He learned to read a room, to anticipate needs, to de-escalate conflict, and to build rapport with strangers. These are not line items on an acting school syllabus, but they are the foundational skills of a believable performer.

I see this as a form of high-intensity data collection. An actor's primary tool is an understanding of the human condition. While his brother Michael pursued a more structured path, becoming a film composer and eventually a college professor, Kevin’s education was empirical. It was a long-form observational study. The question this raises is a significant one: how do we quantify the value of such "unstructured" training in creative professions? If this period was so critical to his development, why is service industry work so consistently devalued as a career stepping stone, rather than being recognized as a legitimate, if unconventional, training ground?

The Correlation Between Past and Present

It’s no coincidence that Bacon shared these reflections at the CREATE conference (an event organized by Nation’s Restaurant News for industry leaders). He wasn't just a celebrity guest parachuted in for name recognition. He was, in a sense, an alumnus of the industry he was addressing. His presence wasn't just aspirational; it was validating. He represents a successful export from their world, a testament to the transferable skills honed within it.

His preference for Cava as a favorite chain and Gennaro, a specific Italian spot on the Upper West Side, further grounds his connection. These aren't generic celebrity endorsements; they're the precise choices of someone who still engages with the industry from a place of genuine appreciation. The data is anecdotal, of course, but it’s consistent with the narrative he presents.

The core of my analysis is this: we have a tendency to retroactively smooth out the career paths of successful people, editing out the messy, non-linear parts. We ignore the years spent waiting tables or driving cabs, viewing them as irrelevant filler. Bacon’s testimony suggests the opposite. It suggests these periods are not noise in the data; they are the signal. They are where the foundational attributes of resilience, observation, and empathy are forged. How many other successful careers, in acting or otherwise, are built on a similar, uncredited "degree" from the service industry or another field of intense, daily human interaction? And what are we missing by systematically ignoring its value?

The Anomaly Is the Signal

Ultimately, the narrative that Kevin Bacon's real education happened in a restaurant is more than just a good story. It's a direct challenge to our conventional models of career development. It suggests that the most valuable training for certain professions, particularly those rooted in understanding people, may not occur in a classroom at all. It happens in the trenches of public-facing work, where the curriculum is unpredictable and the lessons are delivered in real-time. We are conditioned to look for credentials and formal training as predictors of success. But Bacon’s career trajectory implies that for some, the most potent asset is a four-year, front-line education in the messy, chaotic, and deeply informative business of being human. The data is clear: his "college" was unconventional, but the results speak for themselves.