Here's what the data actually tells us about New Jersey's $2 billion ANCHOR program, which is now live.

Another year, another multi-billion-dollar relief program rolls out of Trenton. The Affordable New Jersey Communities for Homeowners and Renters (ANCHOR) program has begun distributing its 2025 payments, with the state treasury confirming the first wave of direct deposits and checks went out on September 15. The headline figures are, as always, designed to impress: over $2 billion in property tax relief, targeting nearly two million households (NJ ANCHOR Program News Today: 2025 Application Opens as Tax Relief Expands). Last year’s program delivered $2.1 billion to 1.8 million residents, and this year’s iteration appears to be on a similar trajectory.

Governor Phil Murphy calls it a core part of his mission to make the state more affordable. State Treasurer Elizabeth Maher Muoio describes it as a “straightforward program with a direct benefit.” On the surface, it’s a simple transaction: the state collects some of the highest property taxes in the nation and then gives a piece of it back. Homeowners can receive up to $1,750, renters up to $700 (NJ ANCHOR Rebate Checks: Are You Getting Yours? How to Apply, Check Status, and Claim Up to $1,750). But when you move past the press releases and dig into the operational mechanics, the word “straightforward” starts to look less like an accurate description and more like a political aspiration. The real story of ANCHOR isn’t the money; it’s the massive, and quietly audacious, logistical operation required to give it away.

The Automation Bet

This year, the state’s primary strategy for achieving efficiency is automation. The Department of the Treasury automatically filed applications for an estimated one million New Jersey residents who were eligible and received benefits last year. In mid-August, confirmation letters went out, effectively telling a huge swath of the population, “You don’t need to do anything; the money is coming.” A Rutgers policy expert, Michael Hayes, correctly noted this is “a good idea” because it circumvents the classic problem of government benefits: friction. Many people who qualify for aid never receive it simply because the paperwork is too daunting or they’re unaware the program even exists.

Auto-enrollment is the state’s bet against that inertia. It’s a clean, elegant solution on paper. But then you notice the outliers. Residents aged 65 or older were not auto-filed. They, along with individuals on Social Security disability, must proactively file using the combined PAS-1 form (a consolidated application that also handles other credits like the “Senior Freeze” and the upcoming Stay NJ program).

And this is the part of the program’s design that I find genuinely puzzling. Why create a two-track system? The stated reason is to consolidate applications for seniors who may be eligible for multiple programs. But it also carves out the state’s most vulnerable population and assigns them the very administrative burden the auto-enrollment system was designed to eliminate. Was it technically too difficult to auto-enroll seniors based on last year’s data? Or is the state assuming that this demographic is more likely to have changing circumstances that require a manual review? The provided data doesn't offer a clear answer.

A System of Deadlines and Discrepancies

For a program billed as simple, the timeline is anything but. There’s the October 31 final deadline to apply. But there was also a critical September 15 deadline for anyone who was auto-enrolled but needed to update their banking information, change their address, or opt for a paper check instead of a direct deposit. If you missed that earlier date, your payment is going to wherever it went last year, period. I've analyzed countless corporate product rollouts, and multiple "soft" and "hard" deadlines like these are often a signal of backend process complexity, not simplicity. It suggests a system that needs to lock in payment data far in advance of the final application cutoff.

The payment structure itself adds another layer of computational work. The benefit isn't a flat amount; it’s a matrix of variables based on homeowner vs. renter status, income level, and age. For homeowners, there are four different potential payments, ranging from $1,000 to $1,750. For renters, the benefit is $450, unless you are 65 or older, in which case it jumps to $700. Each of the nearly two million applications must be correctly sorted into one of these buckets. Last year’s program distributed about $2.1 billion—to be more precise, $2.1 billion to 1.8 million residents. That’s an average of roughly $1,167 per household, but the variance is significant.

The entire apparatus operates under a shadow of impermanence. Monmouth University professor Robert Scott offered the most clinical assessment: “nobody’s gonna turn down free money,” but the rebate is “not guaranteed every year.” It’s a line item in the state budget, subject to the political and economic pressures of the moment. This isn’t an entitlement program; it’s a recurring fiscal decision. What happens in a recession when state revenues crater? Does a program designed to ease affordability become unaffordable for the state itself?

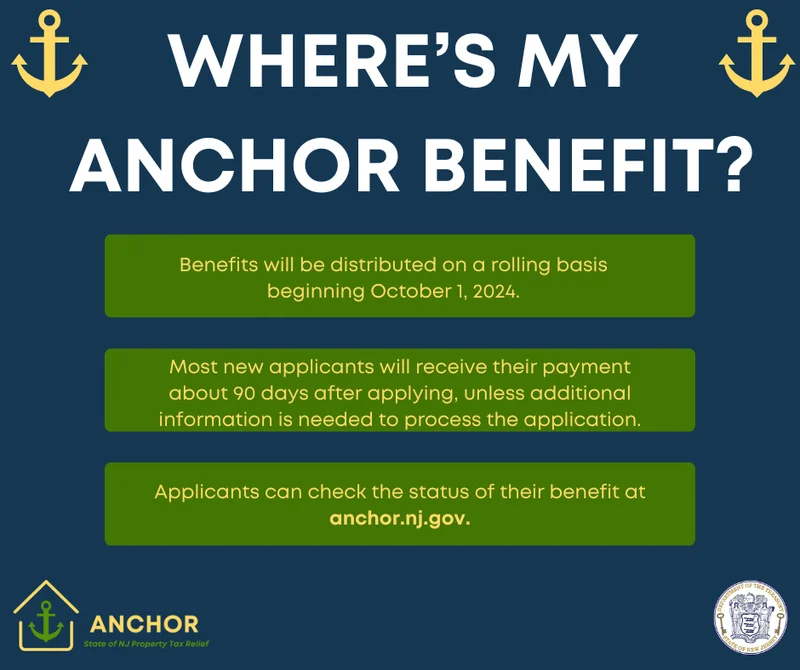

Ultimately, checking your `anchor program status` isn't just about seeing if your check is in the mail. It’s about seeing if you were correctly navigated through this labyrinth. Residents can go online or call a hotline, and the state says it has improved the process with more staff and a callback feature to handle the inevitable flood of inquiries. Imagine the scene: a state employee fielding a call from an 80-year-old who doesn't understand why their neighbor was auto-enrolled but they had to fill out a form. That’s where the program’s theoretical simplicity meets its complex reality.

The Real Audit Is in the Execution

The ANCHOR program is less a tax relief policy and more a massive, annual stress test of the state’s IT infrastructure and logistical capabilities. The Murphy administration has placed an enormous bet on automation to solve the classic government problem of low uptake on benefits. The true measure of success won't be found in the press releases quoting satisfied politicians. It will be in the data we can't see yet: the call wait times at the ANCHOR hotline, the error rate on the 1.8 million payments, and the number of eligible seniors who fail to navigate the manual PAS-1 form and miss out entirely. The numbers we have now are the plan; the data that truly matters will reveal the execution.